Why do a fifth of solar panels degrade rapidly?

An Australian study has explored a critical problem for solar energy: the phenomenon of a significant portion of solar panels failing much faster than expected.

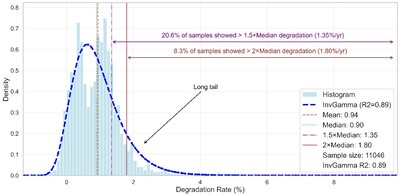

Scientists from UNSW Sydney analysed information from nearly 11,000 different photovoltaic samples globally. What they found was a so-called ‘long tail’ in the probability distribution of the performance data. Appearing on graphs showing the degradation rate per year of the panels, this tail indicates that up to 20% of all samples perform 1.5 times worse than the average.

This means that a significant number of panels do not degrade at a constant rate over a long period of time as might be expected, but instead lose energy or fail much sooner.

The discovery should help to raise the standard of solar panels and make solar farms more cost-effective and reliable.

“Most solar systems are designed to last around 25 years, based on their warranty period,” said Yang Tang, one of the authors of a paper on the subject published in IEEE.

“For the entire dataset, we observed that system performance typically declines by around 0.9% per year. However, our findings show extreme degradation rates in some of the systems.”

Tang said that at least one in five systems degrade at least 1.5 times faster than this typical rate, and roughly one in 12 degrade twice as fast.

“This means that for some systems, their useful life could be closer to just 11 years. Or, in other words, they could lose about 45% of their output by the 25-year mark.”

Why does this happen?

The UNSW team, including Dr Fiacre Rougieux, Dr Shukla Poddar, Associate Professor Merlinde Kay and Tang, a PhD student from the School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering, analysed information collated previously by Dr Dirk Jordan from the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This is a collection of the annual production data from tens of thousands of photovoltaic systems produced globally and includes statistics on performance and maintenance.

The long tail of rapidly failing solar panels in the graphed data is not just a statistical anomaly, according to the UNSW team. Their study found three major reasons for panels to be grouped in the long tail:

1. Interconnected failures

In this scenario, different types of problems interact with each other on an individual panel. For example, if the backsheet (a protective layer on the rear of a module) is damaged, moisture can get in, possibly causing a failure of the electrical junction box and other problems such as cell cracks or corrosion.

This domino effect, where the issues don’t just add up but instead multiply, can be seen to make panels degrade much faster than predicted.

2. ‘Infant mortality’

‘Infant mortality’ refers to rapid failure when modules are relatively new. These panels likely have critical manufacturing defects or material flaws that are not discovered in quality control or testing and therefore fail rapidly — sometimes within just a few years of installation.

3. Minor flaws that go unseen

In this case, a minor flaw, such as a tiny hairline crack in a cell or slightly imperfect soldering, may not cause a problem initially, but can result in a sudden severe performance loss at a random point.

Climate variation ruled out

Importantly, the researchers found that the extreme degradation observed in these panels is not related to the climatic conditions they are exposed to. This rules out the possibility that the data was being skewed by samples placed in extreme environmental locations such as very hot deserts.

“A subset of the data shows information specifically related to solar modules in very hot climates which we know causes higher degradation,” Poddar said.

“However, in other climates, when those hot regions are being excluded from the analysis, we see similar long-tail pattern in the probability distribution of performance degradation rate. This suggests that the issue is consistent regardless of where the panels are operating.”

Poddar explained that current testing standards focus primarily on three parameters: the modules’ response to mechanical stress, extreme temperatures, and exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Panels are also tested often for humidity and response to a standardised amount of sunlight (AM1.5 spectrum).

“But when they are actually operating in real-world conditions there are so many different factors coming into play, and those cascading failures can be very significant,” Poddar said.

“So I think we need to start thinking about different testing standards which would help to ensure we have more resilient types of modules.”

Tackling the problem

For solar farms where hundreds of thousands of panels are installed, the long tail phenomenon represents a large financial risk, creating uncertainty in long-term energy yield and operational budgets.

“With this research, we are hoping to make real impact in three ways,” Poddar said.

“We would like to get even more data from large-scale solar farms to analyse real-world failure rates in even more detail, so we can then make recommendations to the manufacturers of these modules.

“Secondly, we aim to understand different factors contributing to module failures in different climate types to develop [an] early detection system and recommend manufacturers to improve design robustness.

“Thirdly, testing authorities should be informed of real-world degradation patterns across diverse climates and consider combining stress tests to better replicate outdoor operating conditions.”

Creating future-proof dwellings for a harsh climate

Australian research is reinventing what a smart, sustainable living space might look like in an...

Tackling energy insecurity in remote communities

Researchers from Flinders and Macquarie Universities have presented the benefits of community-led...

Paper-thin LEDs that are kinder to the eye

A new, experimental LED is nearly as thin as paper and emits a warm, sun-like glow.